The National Assembly

This content was compiled/created by Soracha Moran

In Brief:

Frustrated by their dealings with the First and Second Estates at the Estates General – particularly their insistence on vote par ordre (where each estate got just one vote for the entire group) – the Third Estate voted among themselves to form a new institution called the National Assembly where the other Estates could join them or not. On 20 June, they had arranged to meet at Versailles where – finding themselves locked out – they met instead at a nearby royal tennis court and took the Tennis Court Oath swearing to continue meeting until they had achieved fairness and justice.

The National Assembly: 1789–1791

Events

Key People

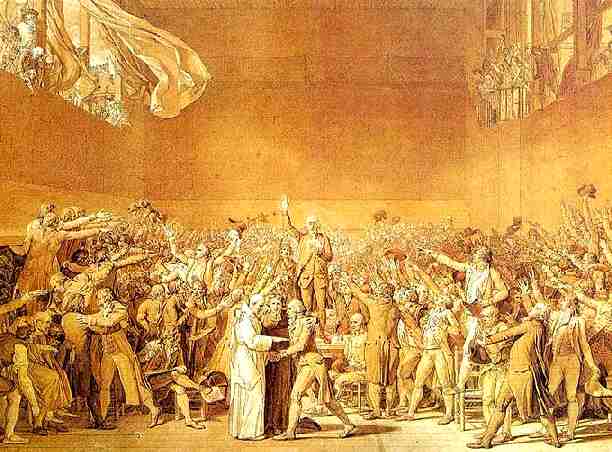

The Tennis Court Oath

Three days after splitting from the Estates-General, the delegates from the Third Estate (now the National Assembly) found themselves locked out of the usual meeting hall and convened on a nearby tennis court instead. There, all but one of the members took the Tennis Court Oath, which stated simply that the group would remain indissoluble until it had succeeded in creating a new national constitution.

Upon hearing of the National Assembly’s formation, King Louis XVI held a general gathering in which the government attempted to intimidate the Third Estate into submission. The assembly, however, had grown too strong, and the king was forced to recognize the group. Parisians had received word of the upheaval, and revolutionary energy coursed through the city. Inspired by the National Assembly, commoners rioted in protest of rising prices. Fearing violence, the king had troops surround his palace at Versailles.

The Bastille

Blaming him for the failure of the Estates-General, Louis XVI once again dismissed Director General of Finance Jacques Necker. Necker was a very popular figure, and when word of the dismissal reached the public, hostilities spiked yet again. In light of the rising tension, a scramble for arms broke out, and on July 13, 1789, revolutionaries raided the Paris town hall in pursuit of arms. There they found few weapons but plenty of gunpowder. The next day, upon realizing that it contained a large armory, citizens on the side of the National Assembly stormed the Bastille, a medieval fortress and prison in Paris.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=poh1_WxNGng&feature=related[/youtube]

Although the weapons were useful, the storming of the Bastille was more symbolic than it was necessary for the revolutionary cause. The revolutionaries faced little immediate threat and had such intimidating numbers that they were capable of nonviolent coercion. By storming one of Paris’s most notorious state prisons and hoarding weapons, however, the revolutionaries gained a symbolic victory over the Old Regime and conveyed the message that they were not to be trifled with.

Lafayette and the National Guard

As the assembly secured control over the capital, it seemed as if peace might still prevail: the previous governmental council was exiled, and Necker was reinstated. Assembly members assumed top government positions in Paris, and even the king himself travelled to Paris in revolutionary garb to voice his support. To bolster the defence of the assembly, the Marquis de Lafayette, a noble, assembled a collection of citizens into the French National Guard. Although some blood had already been shed, the Revolution seemed to be subsiding and safely in the hands of the people.

The Great Fear

For all the developments that were taking place in Paris, the majority of the conflicts erupted in the struggling countryside. Peasants and farmers alike, who had been suffering under high prices and unfair feudal contracts, began to wreak havoc in rural France. After hearing word of the Third Estate’s mistreatment by the Estates-General, and feeding off of the infectious revolutionary spirit that permeated France, the peasants amplified their attacks in the countryside over the span of a few weeks, sparking a hysteria dubbed the Great Fear. Starting around July 20, 1789, and continuing through the first days of August, the Great Fear spread through sporadic pockets of the French countryside. Peasants attacked country manors and estates, in some cases burning them down in an attempt to escape their feudal obligations.

The August Decrees

Though few deaths among the nobility were reported, the National Assembly, which was meeting in Versailles at the time, feared that the raging rural peasants would destroy all that the assembly had worked hard to attain. In an effort to quell the destruction, the assembly issued the August Decrees, which nullified many of the feudal obligations that the peasants had to their landlords. For the time being, the countryside calmed down.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Just three weeks later, on August 26, 1789, the assembly issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a document that guaranteed due process in judicial matters and established sovereignty among the French people. Influenced by the thoughts of the era’s greatest minds, the themes found in the declaration made one thing resoundingly clear: every person was a Frenchman—and equal. Not surprisingly, the French people embraced the declaration, while the king and many nobles did not. It effectively ended the ancien régime and ensured equality for the bourgeoisie. Although subsequent French constitutions that the Revolution produced would be overturned and generally ignored, the themes of the Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen would remain with the French citizenry in perpetuity.

Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen

The Food Crisis

Despite the assembly’s gains, little had been done to solve the growing food crisis in France. Shouldering the burden of feeding their families, it was the French women who took up arms on October 5, 1789. They first stormed the city hall in Paris, amassing a sizable army and gathering arms. Numbering several thousand, the mob marched to Versailles, followed by the National Guard, which accompanied the women to protect them. Overwhelmed by the mob, King Louis XVI, effectively forced to take responsibility for the situation, immediately sanctioned the August Decrees and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. The next day, having little choice, the royal family accompanied the crowd back to Paris. To ensure that he was aware of the woes of the city and its citizens, the king and his family were “imprisoned” in the Tuileries Palace in the city

Though they focused on the king as figurehead, most of the revolutionaries were more against the nobles than the king. Everyday people in France had limited interaction with royalty and instead placed blame for the country’s problems on the shoulders of local nobility. A common phrase in France at the time was, “If only the king knew,” as though he were ignorant of the woes of the people. It was partly owing to this perspective that the assembly attempted to establish a constitutional monarchy alongside the king, rather than simply oust him and rule the nation itself.

The National Assembly and the Church

Over the next two years, the National Assembly took a number of progressive actions to address the failing economy and tighten up the country. A number of them targeted the Catholic Church, which was at the time one of the largest landholders in France. To jump-start the economy, the state in February 1790 confiscated all the church’s land and then used it to back a new French currency called the assignat. In the beginning, at least, the assignat financed the Revolution and acted as an indicator of the economy’s strength.

A short time later, in July 1790, the French Catholic Church itself fell prey to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, a decree by the National Assembly that established a national church system with elected clergy. The country was divided into eighty-three departments, each of which was governed by an elected official and represented by an elected bishop. The voting for these positions was open to anyone who met certain relatively lenient criteria, such as property ownership.

The Assembly’s Tenuous Control

Despite the National Assembly’s progress, weaknesses were already being exposed within France, and the Great Fear and the women’s march on Versailles demonstrated that perhaps the assembly didn’t have as much control as it liked to think. The revolution that the assembly was overseeing in Paris was run almost exclusively by the bourgeoisie, who were far more educated and intelligent than the citizens out in the country. Although the August Decrees helped assuage the peasants’ anger, their dissatisfaction would become a recurring problem. The differing priorities that were already apparent foreshadowed future rifts.

Most notable among the assembly’s controversial priorities was its treatment of the churches. Although France as a whole was largely secular, large pockets of devoutly religious citizens could be found all over the country. By dissolving the authority of churches, especially the Catholic Church—a move that greatly angered the pope—the assembly seemed to signal to the religious French that they had to make a choice: God or the Revolution. Although this was likely not the case, and certainly not the assembly’s intent, it nevertheless upset many people in France.

A poster form the French Revolution declaring Liberty, Equality, Fraternity or Death.

Factionalism and War

On Oct. 1, 1791, the Legislative Assembly convened. Some members joined the various political clubs of Paris, such as the Feuillants and Jacobins. Most deputies were middle-of-the-roaders, swayed by the more radical clubs and by the Girondists. Jacobinism was gaining in this period; “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” became a catch phrase.

Meanwhile abroad, early sympathy for the Revolution was turning to hatred. Émigrés incited the courts of Europe to intervene; in France, war was advocated by the royalists as a means to restore the old regime, but also by many republicans, who either wished to spread the revolution abroad or hoped that the threat of invasion would rally the nation to their cause. The Feuillant, or right-wing, ministers fell and were succeeded by those later called Girondists. On Apr. 20, 1792, war was declared on Austria, and the French Revolutionary Wars began. Early reverses and rumors of treason by the king again led Parisian crowds to direct action.

An abortive insurrection of June 20, 1792, was followed by a decisive one on Aug. 10, when a crowd stormed the Tuileries and an insurrectionary commune replaced the legally elected one. Under pressure from the commune, the Assembly suspended Louis XVI and ordered elections by universal manhood suffrage for a National Convention to draw up a new constitution. Mass arrests of royalist sympathizers were followed by the September massacres (Sept. 2–7), in which frenzied mobs entered jails throughout Paris and killed approximately 2,000 prisoners, many in grisly fashion.

The Republic

On Sept. 21, 1792, the Convention held its first meeting. It immediately abolished the monarchy, set up the republic, and proceeded to try the king for treason. His conviction and execution (Jan., 1793) reinforced royalist resistance, notably in the Vendée, and, abroad, contributed to the forming of a wider coalition against France. The Convention undertook the foreign wars with vigor but was itself torn by the power struggle between the Girondists and the Mountain (Jacobins and extreme left). The Girondists were purged in June, 1793. A democratic constitution was approved by 1.8 million voters in a plebiscite, but it never came into force.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

History@Banagher College, Coláiste na Sionna.

The URI to TrackBack this entry is: http://teachnet.eu/tobrien/about/revolutions/the-french-revolution/the-national-assembly/trackback/

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.