Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

This content was created/compiled by Liam Tierney

In Brief:

Thomas Jefferson was a follower of the Enlightenment. He became famous as the main author of the Declaration of Independence and went on to become the third president of America. He had many talents including as a horticulturist, political leader, architect, archaeologist, paleontologist and inventor.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

(Born April 13, 1743, at Shadwell, Virginia; died July 4, 1826, Monticello)

Family

His father Peter Jefferson was a successful planter and surveyor (an occupation shared with George Washington) and his mother Jane Randolph a member of one of Virginia’s most distinguished families. Having inherited a considerable landed estate from his father, Jefferson began building Monticello when he was twenty-six years old. Three years later, he married Martha Wales Skelton, with whom he lived happily for ten years until her death. Their marriage produced six children, but only two survived to adulthood. Jefferson, who never remarried, maintained Monticello as his home throughout his life, always expanding and changing the house. Jefferson inherited slaves from both his father and father-in-law. In a typical year, he owned about 200, almost half of them under the age of sixteen. About eighty of these lived at Monticello; the others lived on adjacent Albemarle County plantations, and on his Poplar Forest estate in Bedford County, Virginia. Jefferson freed two slaves in his lifetime and five in his will and chose not to pursue two others who ran away. All were members of the Hemings family; the seven he eventually freed were skilled tradesmen.

Education and Profession

Having attended the College of William and Mary, Jefferson practiced law and served in local government as a member of the House of Burgesses in his early professional life. As a member of the Continental Congress, he was chosen in 1776 to draft the Declaration of Independence, The document proclaims that all men are equal in rights, regardless of birth, wealth, or status, and that the government is the servant, not the master, of the people.After Jefferson left Congress in 1776, he returned to Virginia and served in the legislature. Elected governor from 1779 to 1781.During the brief private interval in his life following his governorship, Jefferson wrote Notes on the State of Virginia. In 1784, he entered public service again, in France, first as trade commissioner and then as Benjamin Franklin’s successor as minister. During this period, he studied European culture, sending home to Monticello, books, seeds and plants, statues and architectural drawings, scientific instruments, and information.

In 1790 he accepted the post of secretary of state under his friend George Washington. His tenure was marked by his opposition to the pro-British policies of Alexander Hamilton. In 1796, as the presidential candidate of the Democratic Republicans, he became vice-president after losing to John Adams by three electoral votes.

Four years later, he defeated Adams and became president.

Later Years

Jefferson was succeeded as president in 1809 by his friend James Madison, and during the last seventeen years of his life, he remained at Monticello. During this period, he sold his collection of books to the government to form the nucleus of the Library of Congress. Jefferson embarked on his last great public service at the age of seventy-six, with the founding of the University of Virginia. He spearheaded the legislative campaign for its charter, secured its location, designed its buildings, planned its curriculum, and served as the first rector.

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, just hours before his close friend John Adams, on the fiftieth anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. He was eighty-three years old, the holder of large debts, but according to all evidence a very optimistic man.

Beyond mere activity, Jefferson spent his closing years engaged in a variety of intellectual pursuits. Henry Adams, piercing as ever, drolly described Jefferson as “a martyr to the disease of omniscience,” and it was a “disease” which Jefferson pursued in earnest during retirement as at no other time. Whether it was dabbling in a variety of classical and modern languages, reading up on the ancient philosophers and playwrights, collecting and classifying fossils or keeping extensive meteorological records, he seemingly had a hand in every

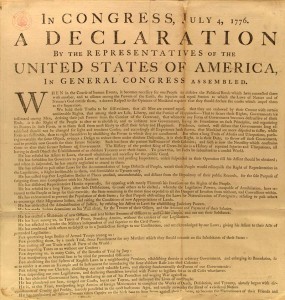

The Declaration

Signing

Contrary to popular belief, the Declaration of Independence was not signed on July 4th. On that day, the Declaration of Independence was officially adopted by the Continental Congress. On July 19th, the Continental Congress voted to have it engrossed and signed. The document was ready for delegates’ signatures by August 2nd, and that is the earliest date at which Jefferson and the other delegates present in Philadelphia could have signed it.

On the evening of July 4, 1776 a manuscript copy of the Declaration of Independence was taken to Philadelphia printer, John Dunlap. By the next morning finished copies had been pulled and delivered to Congress for distribution. The number printed is not known, though it must have been substantial; the broadsides were distributed by members of Congress throughout the Colonies. Post riders were sent out with copies of the Declaration, and General Washington, then in New York, had several brigades of the army drawn up at 6 p.m. on July 9 to hear it read. The Declaration was read from the balcony of the State House in Boston on July 18 but did not reach Georgia until mid August. Twenty-four original copies of what is referred to as the “Dunlap broadside” are still in existence.

The Engrossed Declaration

By July 9 all thirteen colonies had signified their approval, and so on July 19 Congress was able to order that the Declaration be “fairly engrossed on parchment. And that the same, when engrossed, is signed by every member of Congress.” Timothy Matlack is believed to be the engrossed of the Declaration. On August 2nd the document was ready, and the journal of the Continental Congress records that “The declaration of independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed.” Following the signing, it is believed the document accompanied the Continental Congress during the Revolution and remained with government records following the war. During the War of 1812 it was kept at a private residence in Leesburg, Virginia and during World War II it was housed at Fort Knox. Today, the original document is kept in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

History@Banagher College, Coláiste na SionnaThe URI to TrackBack this entry is: http://teachnet.eu/tobrien/about/revolutions/the-american-revolution/thomas-jefferson/trackback/

3 Comments Leave a comment.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thomas Jeffersons, George Washington and Wolfe Tones wives were all called Martha!! Weird!!

i never knew there was a coin with thomas jeffersons face on it.

very interesting lots of good stuff in the family life