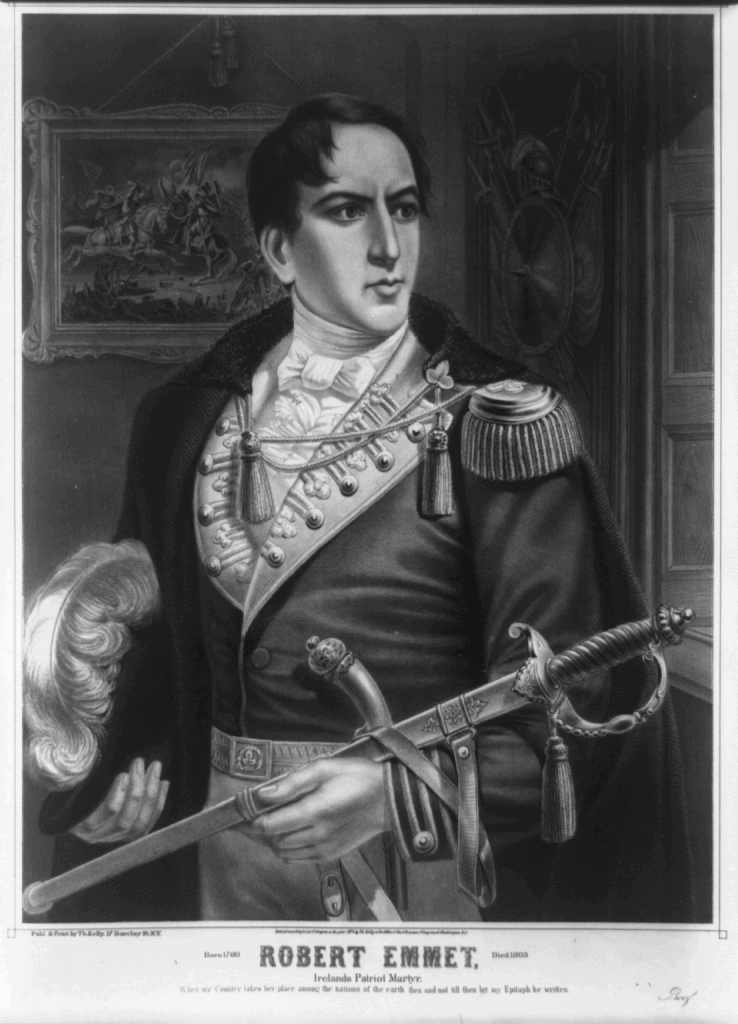

Robert Emmet

This content was created/compiled by Hilary Newcombe.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

In Brief:

After the Act of Union (1801) abolished the Irish parliament, forcing Ireland to become part of Britain, some Irish opponents of the Union tried to break it by force. The most famous of these was a young man called Robert Emmett (brother of one of the United Irishmen, Thomas Addis Emmet). He had bought weapons and amunition and explosives to stage a rebellion. However, some of these exploded prematurely in one of the Dublin houses where they were stored forcing Emmett to bring forward his plans. The rising took place on 23 July 1803, but was generally a disaster and was easily crushed by the military with only a few shots fired. Although Robert Emmett escaped, he was captured a month later at the home of his fiancée Sarah Curran. He was tried in Dublin where after he was sentenced to death at a corupt trial. It was then that he made his famous ‘speech from the dock’ which was to inspire future rebellions both in Ireland and abroad. Robert Emmett was convicted of treason before being hung and then beheaded at Thomas Street, Dublin on September 20th 1803.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_IZZ9GaG89I&feature=player_embedded#![/youtube]

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet was born in Dublin on 4 March 1778.

He was the youngest son of Dr Robert Emmet (1729–1802), and Elizabeth Mason (1740–1803).

His dad was a state physician, so the family were financially comfortable, with a house at St Stephen’s Greenand a country residence near Milltown.

One of his older brothers was a nationalist called Thomas Addis Emmet, a close friend of Theobald Wolfe Tone, who visited the house a lot when Robert was a child.

Robert Emmet entered Trinity College, Dublin in October 1793, at the age of fifteen.

In December 1797 he joined the College Historical Society, a debating society.

While he was at college, his brother Thomas and some of his friends became involved in political activism.

Robert himself became secretary to a United Irish society in college, and was expelled in April 1798 as a result.

After the 1798 rising, Robert Emmet was involved in reorganizing the defeated United Irish Society.

In April 1799 a warrant was issued for his arrest, and he escaped. Soon after, he travelled to the continent in the hope of securing French military aid.

His efforts were unsuccessful, and so he returned to Ireland in October 1802.

In March the following year, he began preparations for another rising.

1803 rebellion

After he returned to Ireland, Robert began to prepare a new rebellion, with fellow revolutionaries Thomas Russell and James Hope.

He began to manufacture weapons and explosives at a number of locations in Dublin and even invented a folding pike which could be concealed under a cloak, which was fitted with a hinge.

Unlike in 1798, the preparations for the uprising were successfully concealed, but a premature explosion at one of Emmet’s arms depots killed a man and forced Emmet to bring forward the date of the rising before the police got suspicious.

Emmet wasn’t able to secure the help of Michael Dwyer’s Wicklow rebels, and many Kildare rebels who had arrived turned back, due to the scarcity of firearms they had been promised, but the rising went ahead in Dublin on the evening of July 23, 1803.

Failing to seize Dublin Castle, which wasn’t defended very well, the rising amounted to a large-scale riot in the Thomas Street area.

Emmet witnessed a dragoon being pulled from his horse and piked to death, the sight of which prompted him to call off the rising to avoid further bloodshed. However, he had lost control of his all followers and in one incident, the Lord Chief Justice of Ireland, Lord Kilwarden, the judge who granted habeas corpus to Wolfe Tone in 1798, was dragged from his carriage and hacked to death. Clashes continued into the night until finally quelled by the military at the estimated cost of twenty military and fifty rebel dead.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Emmet’s fate

Emmet fled into hiding but was captured on 25 August, near Harold’s Cross.

He endangered his life by moving his hiding place from Rathfarnam to Harold’s Cross so that he could be near his sweetheart, Sarah Curran.

He was tried for treason on 19 September; the Crown repaired the weaknesses in its case by secretly buying the assistance of Emmet’s defense attorney,Leonard Macnally, for £200 and a pension.

However, his assistant Peter Burrowes could not be bought and pleaded the case as best he could.

After he had been sentenced Emmet delivered a speech, the Speech from the Dock, which is especially remembered for its closing sentences and secured his posthumous fame among executed Irish republicans. However no definitive version was written down by Emmet himself.

An earlier version of the speech was published in 1818, in a biography on Sarah Curran’s father John.

On 19 September, Emmet was found guilty of high treason, and Chief Justice Lord Norbury’s death sentence required that Emmet was to be hung, drawn and quartered.

The following day, 20 September, Emmet was executed in Thomas Street.

He was hung and then beheaded once dead. The remains were then secretly buried. The whereabouts of his remains is still a mystery.

It was suspected that it had been buried secretly in the vault of a Dublin Anglican church. When the vault was inspected in the 1950s, a headless corpse that could not be identified, but which was suspected to be Emmet’s, was found.

In the 1980s the church was turned into a night club and all the coffins removed from the vaults.

What was done with the mysterious corpse? No one knows.

Even though Emmet’s rebellion was a complete failure, he became an heroic figure in Irish history. His speech from the dock is widely quoted and remembered, especially among Irish nationalists.

Emmet’s housekeeper, Anne Devlin, is also remembered in Irish history for enduring torture without providing information to the authorities.[4]

Robert Emmet wrote a letter from his cell in Kilmainham Jail, Dublin on 8 September 1803.

He addressed it to “Miss Sarah Curran, the Priory, Rathfarnham” and handed it to a prison warden, George Dunn, whom he trusted to deliver it. Dunn betrayed him and gave the letter to the government authorities, an action that nearly cost Sarah Curran her life.

His attempt to hide near Sarah Curran, which cost him his life, and his parting letter to her made him into a romantic character, which appealed to the Victorian Era’s appetite for Romanticism, which prolonged his fame.

His story became the subject of stage melodramas during the 19th century, most notably Dion Boucicault’s hugely inaccurate 1884 play Robert Emmet

Washington Irving, one of America’s greatest early writers, devoted “The Broken Heart” in hismagnum opus The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon to the romance between Emmet and Sarah Curran, using it as an example of how a broken heart can be fatal.

Robert Emmet’s older brother, Thomas Addis Emmet would emigrate to the United States shortly after Robert’s execution and would eventually serve as the New York State Attorney General.

His great-grand-nieces are the prominent American portrait painters Lydia Field Emmet, Rosina Sherwood Emmet, Jane Emmet de Glehn and Ellen Emmet Rand. Robert Emmet’s great-great nephew was the American playwright Robert Emmet Sherwood.

Places named after Emmet include Emmetsburg, Iowa, Emmet County, Iowa, and Emmet County, Michigan. There is a statue of Emmet in front of the California Academy of Sciences, in Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Sarah Curran

Sarah Curran (1782-1808) was the youngest daughter of John Philpot Curran, an eminent Irish lawyer. She met Emmet through her brother Richard, who was a follow student at Trinity College. Her father considered Emmet unsuitable, and their courtship was conducted through letters and clandestine meetings. When her father discovered that Sarah was secretly engaged, he treated her so harshly that she had to take refuge with friends in Cork, where she met and married Captain Robert Sturgeon in November 1805. They had a child who died in infancy. Sarah died of consumption (tuberculosis) on May 5, 1808.

September, 1803

My dearest Love,

I don’t know how to write to you. I never felt so oppressed in my life as at the cruel injury I have done you. I was seized and searched with a pistol over me before I could destroy your letters. They have been compared with those found before. I was threatened with having them brought forward against me in Court. I offered to plead guilty if they would suppress them. This was refused. My love, can you forgive me?

I wanted to know whether anything had been done respecting the person who wrote the letter, for I feared you might have been arrested. They refused to tell me for a long time. When I found, however, that this was not the case, I began to think that they only meant to alarm me; but their refusal has only come this moment, and my fears are renewed. Not that they can do anything to you even if they would be base enough to attempt it, for they can have no proof who wrote them, nor did I let your name escape me once. But I fear they may suspect from the stile [style], and from the hair, for they took the stock [Emmet’s cravat into which Sarah had sewn a lock of her hair] from me, and I have not been able to get it back from them, and that they may think of bringing you forward.

I have written to your father to come to me tomorrow. Had you not better speak to himself tonight? Destroy my letters that there may be nothing against yourself, and deny having any knowledge of me further than seeing me once or twice. For God’s sake, write to me by the bearer one line to tell me how you are in spirits. I have no anxiety, no care, about myself; but I am terribly oppressed about you. My dearest love, I would with joy lay down my life, but ought I to do more? Do not be alarmed; they may try to frighten you; but they cannot do more. God bless you, my dearest love.

I must send this off at once; I have written it in the dark. My dearest Sarah, forgive me.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

History@Banagher College, Coláiste na Sionna

The URI to TrackBack this entry is: http://teachnet.eu/tobrien/about/revolutions/revolution-in-ireland/robert-emmet/trackback/

2 Comments Leave a comment.

Leave a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

cool!! i had no idea that robert emmets brother was friends with wolfe tone!!!

they don’t know where his remains are!thats really interesting!